By Ndubuisi Christian Ani, PhD

By 12 May 2019, South Sudan is expected to reconstitute a new transitional government in line with a revitalized deal reached on 12 September 2018. But the delays in finalizing the pre-arrangements have exposed the fragility of the new deal and the limited international measures to ensure the compliance of the warring parties who have broken previous deals.

Thus far, the conflict parties are yet to overcome ethnic and party tensions to form the unified force to provide security to the political rivals that will assume office by May 2019 in Juba and other locations. Like the situation in 2016, violence could break out if officials resort to their party-based security forces.

While violence has reduced, reports of ceasefire violations and continued human rights abuses further raise alarm over the commitment of the warring parties. Additionally, key institutions such as the Independent Boundaries Commission (IBC) haven’t determined the number and boundaries of states as required by the new deal.

At the United Nations (UN) Security Council (UNSC) meeting on 8 March 2019, David Shearer, the UN Envoy to South Sudan stressed that there are no alternative plans in place beside the current deal. He urged the international community not to allow the peace deal to unravel because ‘a peace that falters will generate frustration, anger and a possible return to violence, that could equal that which occurred in 2013 and 2016.’

The international community including the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the Africa Union (AU) and the UN have to agree on accountability mechanisms and speak with one voice to assert the repercussions of a failed deal to the warring parties.

One of the positive impacts of the revitalized agreement on the resolution of conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS) is the relative reduction of violence. David Shearer affirmed that ‘opposition politicians from different parties are moving freely around Juba without hindrance and are taking part in the various meetings as part of the peace process’.

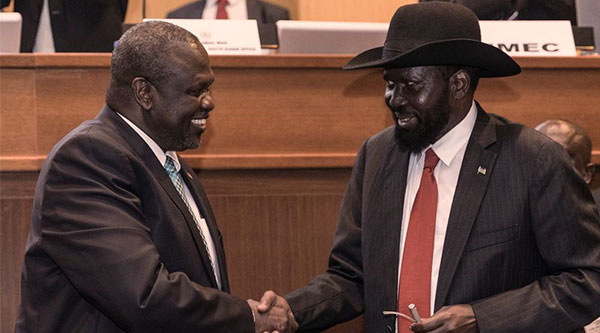

In October 2018, Dr. Riek Machar went to Juba to participate in the peace celebration. This was his first visit to South Sudan since July 2016 when fighting resurged between his forces and that of President Salva Kiir thereby stalling the 2015 peace deal.

Despite the relative peace however, some clashes have been reported leading the IGAD Special Envoy to South Sudan, Ismail Wais to plead for adherence to the ceasefire deal. The violence has particularly been intense in Yei in Central Equatoria between government forces and the National Salvation Front (NAS) forces led by Gen Thomas Cirilo Swaka.

Gen Cirilo had refused to sign the September 2018 deal along with other non-signatories such as the South Sudan National Democratic Alliance (SSNDA) and the Paul Malong’s South Sudan United Front (SSUF). Gen Cirilo argued that the new deal is merely a power-sharing arrangement between Kiir and Machar and that it does not devolve powers to other actors. He insists that NAS will continue the armed struggle until a new deal is negotiated. Indeed, the major threat to the peace deal in South Sudan is the uncertainty surrounding how to effectively manage the growth and interests of armed groups emerging from the Kiir and Machar camps and seeking greater representation since violence first erupted in 2013.

The ongoing fighting in Yei and the continued movement of troops outside the cantonment areas may lead to broader confrontations across the country. On 28 February, the South Sudan Catholic Bishops released a message raising alarm that the implementation of the peace deal is slow and that ‘all parties are involved either in active fighting or preparations for war’

Reports have also shown that the warring parties are recruiting and training new fighters in violation of the deal. In December 2018, four officials of the Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism (CTSAMVM) who were investigating the reports were detained and tortured by government forces at an army base in Luri near Juba.

Concerns over the sustainability of the new deal is among the main reasons why international partners such as the Troika are reluctant to fund the new peace deal after providing support to the failed 2015 deal. On 20 February 2019, the Troika which is made up of the United States, Norway, and the United Kingdom issued a joint statement warning that the ‘renewed violence risks undermining the peace agreement and lowers confidence of the Troika and other international partners in the parties’ seriousness and commitment to peace.’

The government’s history of excessive spending on items of lesser priority is also a cause for concern for many donors. Recently, over $135,000 of the funds dedicated to implement the peace deal was used to renovate houses of Vice President Taban Deng and the widow of late Dr John Garang, Rebecca Nyandeng De Mabior, who will be part of the country’s five vice presidents.

The government have only pledged $1.6 million out of the $285 million budget it recently estimated for the implementation of the deal. Just last year, the government in July 2018 gave $16 million to 400 members of parliament as car loans while civil servants endured several months without salary. Such frivolous spending raise concern about the willingness to implement the core aspects of the deal.

More worrying about the peace process is that some of the relevant pre-transitional arrangement have faced significant delays. The Independent Boundaries Commission (IBC) which has a critical role to play in determining the number and borders of states is yet to finalize the process. It effectively stalls the determination of the composition of the Council of States. This is required to address the tensions created when President Salva Kiir unilaterally created 32 states in defiance of the existing 10 states and the formula for power-sharing set out by the August 2015 agreement. The work of the IBC, as stipulated in the deal, should have been finalized on 12 December 2018.

It is also uncertain whether the IBC will automatically be transformed into the Referendum Commission on Number and Boundaries of States (RCNBS). This is to pave way for a referendum to determine the numbers and boundaries of states.

Additionally, the failure to complete the process of unifying the forces in South Sudan raises concerns about how the security of opposition parties will be guaranteed if they assume office in Juba in May 2019.

As it stands, members of IGAD, AU and the UN are deeply divided over enforcement measures to take on South Sudan. Whether the transitional government is reconstituted in May 2019 or shifted to a later date for the finalization of pre-arrangements, the international community have to be unanimous in outlining the consequences of a return to violence.

Specifically, IGAD has to prioritize negotiations regarding the unification of armed forces including the possibility of third-party protection force in Juba. This includes finding a solution to manage the interests of the non-signatories to the R-ARCSS.